I am afraid I must dissent from the ever-rising hallelujah chorus of adulation being orchestrated by and for the chief justice of Canada, Beverley McLachlin.

I admired her lower court rulings in favour of free speech, and in the only case she helped adjudicate in which I was involved, she and her whole court supported my right to sue the authors of the infamous farrago of lies in the Hollinger International special committee report for libel, in Canada. This decision enabled me to negotiate a settlement of $5 million, an unheard of figure in Canadian legal history, such were the proportions of the libel I endured. (I would have to be a recluse to be unaware of less condign positions the chief justice has advocated that concerned me in her role as chair of the advisory board of the Order of Canada, but that is not germane here.)

Beverley McLachlin has been a judge since just before the Charter was proclaimed, and became chief justice of Canada in 2000. The Supreme Court website carries her lecture of May 5, 2001, in which she exhorted the community of judges (her husband is the executive director of the Canadian Superior Courts Judges’ Association, which represents, educates and handles public relations for about a thousand judges), to step fully into their new role. In this seminal document, the chief justice said nothing but the truth in remarking that “the law-making role of the judge has dramatically expanded” and now consisted of “invading the domain of social policy, once perceived to be the exclusive right of Parliament and the legislatures.”

No one can say she did not warn us or that she has not followed through on what she urged. It was a matrix for a mighty usurpation of the authority of the legislator, and of the public, as Chief Justice McLachlin’s court has rushed to occupy the vast open prairies between what has been legislated and what remained within the public’s liberty to act freely.

In her historic lecture of 2001, she cited an Institute for Research in Public Policy poll, which found that 77 per cent of Canadians were satisfied with the Supreme Court. Such a facile argument affronts the whole nature of an independent judiciary. These high court judges are appointed for service to age 75 precisely to immunize them from public opinion and enable them to make whatever decisions they collectively find appropriate, without a concern for public opinion. Their approval rating was so high because most people despise politicians, have bought the bromides about the rule of law and assume that the judges are competent because their decisions rarely get much attention, despite a good deal of judicial grandstanding to publicize them. Citizens have to believe that some part of government works or they would become quite demoralized.

Even the chief justice shyly wondered in her manifesto of May 5, 2001, whether the courts, which have much smaller resources than legislatures, “are the best institutions to decide complex social policy questions.” Of course they are not, and neither Trudeau nor any other sane person ever suggested that they are or have any authority to do anything of the kind. But undaunted by the looming negative answer to her own rhetorical question, the chief justice gamely took on the role of doing what the court is not qualified to do, in the name of “the law, majestic and eternal.” (No one who has had anything to do with our court system can easily escape the suspicion that many of our judges are “the zeitgeist in robes,” as my friend George Jonas put it, thriving on their sinecures. There isn’t much majesty about most of them.)

There is no alternative to a reasonable version of the rule of law, but as it has evolved, the law is often a proverbial ass and a spavined ass, and many judges, sadly, are decayed servitors, though probably more or less well-intentioned. The legal profession is a cartel that writes, enacts, argues and judges an ever larger and more onerous body of laws and regulations and sanctions, generating an increasing share of the GDP for their (poorly) self-governing profession, a vast business swaddled now in McLachlinese claptrap about being “majestic, eternal.” As the supreme champion of the exaltation of her profession and occupation, the chief justice has earned the gratitude of her confreres.

The chief justice has been drinking too much of her own bathwater

But in order for a country to get the government it deserves, power must reside in the hands of those whom the people have elected. McLachlin’s effort to mould Trudeau’s anti-separatist wheeze into a blank cheque to rewrite Canada’s social policy is a scandal legitimized only by the lassitude of a prime minister who has terrorized the living Jehovah out of his own cabinet and caucus and muzzled Parliament, but has acquiesced in rule by a gonzo judiciary and an officious bureaucracy of what the Marquess of Salisbury called “imbecile punctilios.”

The media don’t notice and the public don’t care, while the legislators have been inexplicably slow to vacate trespassing court decisions by invoking the notwithstanding clause (apart, of course, from Quebec’s intermittent enthusiasm for suppressing the liberty of expression of its English-speaking people), freeing McLachlin to remake the country. No doubt many of her ground-breaking judgments have been beneficial, but that is not exactly the point. Nor is this the place for an analysis of her court’s many trail-blazing judgments, though I did comment here recently on the absurd decisions that her court can determine the conditions under which people may commit suicide, and that the right of association in the Charter entitles public service employees to strike. There is evidence that the chief justice has been drinking too much of her own bathwater, as in her provocative reference this week to Canada having committed “cultural genocide” against native people, and her ex cathedra complaints earlier this year about the proximity to her court of a monument to the victims of communism.

Canadians will be unpleasantly electrified eventually by this official roundel of abdications and arrogations, and will tire of the negligence and trespass of their public officials. The chief justice’s integrity is not at issue and Stephen Harper should not have tried to impugn it over the Nadon affair. But she is exercising an authority she does not legitimately possess. No one will be hanged to lamp posts, nor will cobblestones be thrown at the police (this is Canada); she will have earned her pension; but as a parliamentary democracy, we can do better than this.

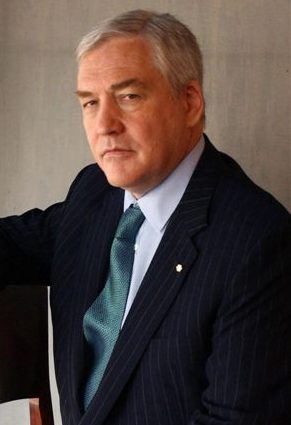

Conrad Black is the founder of the National Post. His columns regularly appear in the National Post on Saturdays. For more opinion from Conrad Black, tune into The Zoomer on VisionTV (a property of ZoomerMedia Ltd.), Visiontv.ca.

Mr. Black graciously allowed us to reprint this article on CFN.

She is a horrible Justice.

She is no more a horrible Justice than Conrad Black is a horrible human being. He thinks he’s above everyone else and deserves “special” treatment.

Conrad Black has written quite a few insightful columns over the last year or so, but this isn’t one of them. An important function of the Supreme Court is to protect the rights of Canadians from wanna-be despots like our Prime Minister Harper. Without the Supreme Court and Beverley McLachlin, Canada would strongly resemble a banana republic by now.

Off topic… Jamie, I’m finding the CFN website difficult and irritating to navigate. Very slow loading, way too many old items to scroll through, and I can barely see what I am trying to post while typing.

Furtz I’ve had reports good and bad about the new site design; mostly good. It’s a responsive structure so it doesn’t handle like the old one.

If you wish send me a screen shot or email with your particular issue. If you have low memory on your computer or have an older machine that can be an issue as it might not be keeping up. CFN is now geared more for mobile and tablets.

Lovely–a convicted felon, who renounced his Canadian citizenship, takes Canada’s chief justice to task. “McLachlin has emasculated the high court of Parliament and led a coup d’état.” Hahaha–good one.. Actually No: that honour belongs to Stephen Harper, with his prorogations, omnibus bills and general contempt for the democratic processes of Parliament. A closet fascist (“I make the rules”), Harper would do away with the Supreme Court too, if he could. Sad to say, Mr. Black has become a misguided windbag in his elder years.